The Amazon Soundscape

In the summer of 2012 I had the opportunity of joining an annual ecological survey of the Pacaya-Samiria National Reserve (PSNR) in Peru under the umbrella of Operation Wallacea. PSNR is contained within the confluence of the Marañón and Ucayali Rivers where the main-stem of the Amazon River originates.

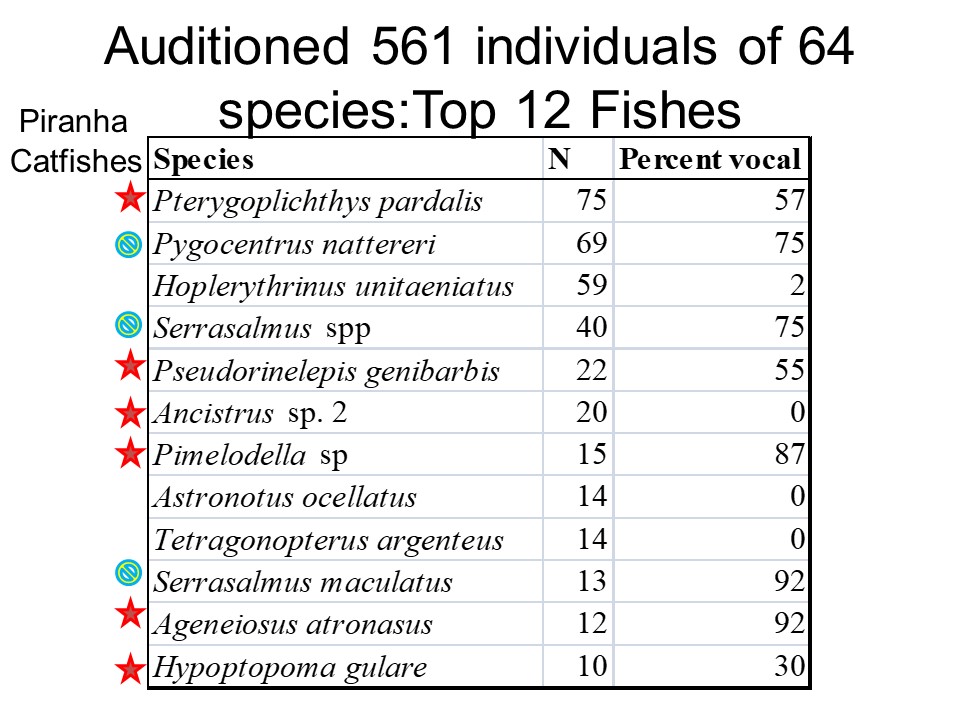

As far as I'm aware no one had ever recorded the natural soundscape in the region, and few studies have been published to date in the entire Amazon. So my plan was to piggyback on the fishing survey conducted by Operation Wallacea with the goal of both recording the natural soundscape and auditioning as many species of fishes as I could.

|

|

|

Base camp

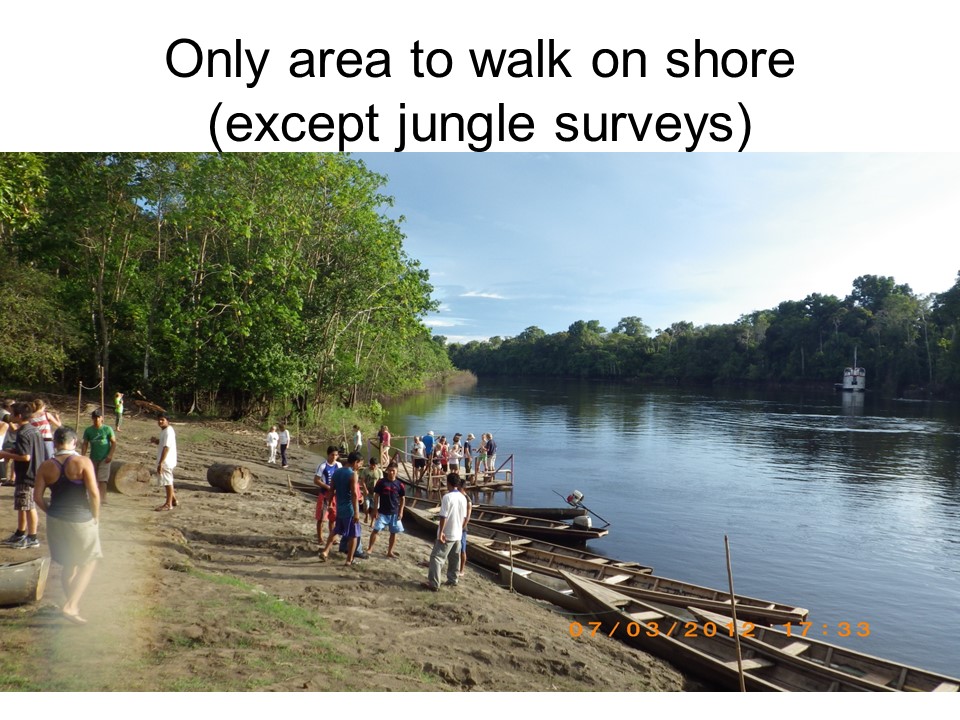

I was a bit disappointed when I first learned I would be staying at that site for my entire 4 week expedition instead of visiting different sites in the reserve, but I soon

learned that it was just fine, because every day was different! That's because I was there doing the low water season when the vast flooded forest recedes rapidly, resulting in

migrations of fishes moving out of the flooded forest and lakes and into the Rivers. Different fishes would begin migrating at different times, so that I got to see lots of different

species despite sampling within only a 5 km region around the base station. For example, below you can view a short movie clip of vast number of Palometa fish (multiple species)

migrating out of

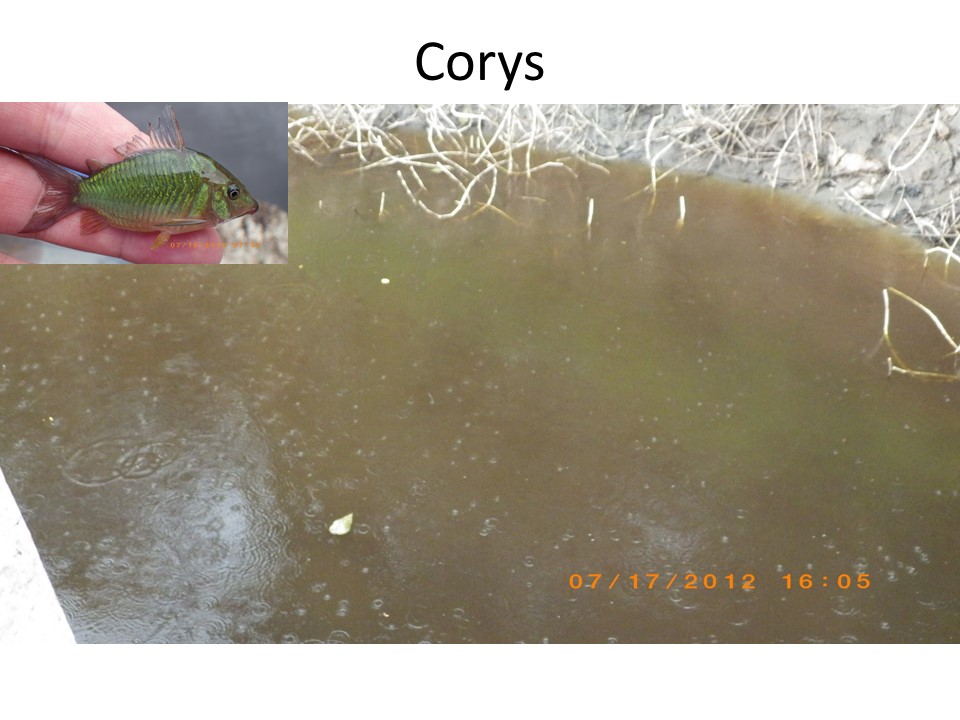

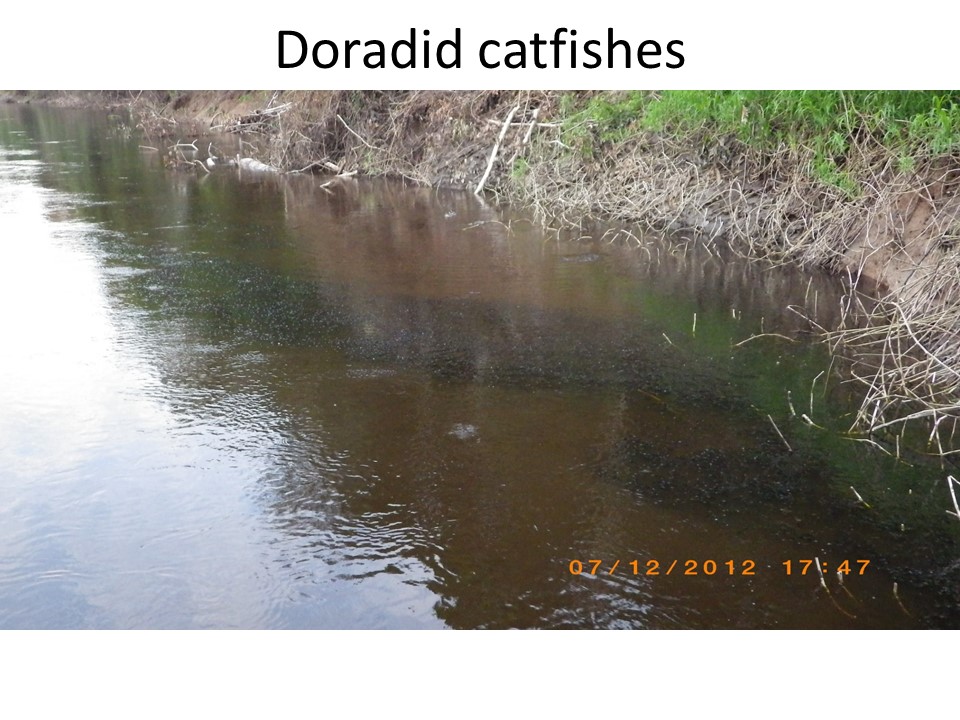

the lake and forest and moving downstream. Example photographs taken from on deck of the Rio Amazonas of different species of fishes migrating along the shore down river illustrate their

tendency to remain close to the surface (note many of them depend on air gulped at the surface for respiration, and some will even drown if they can't get air).

|

|

|

|

Sampling

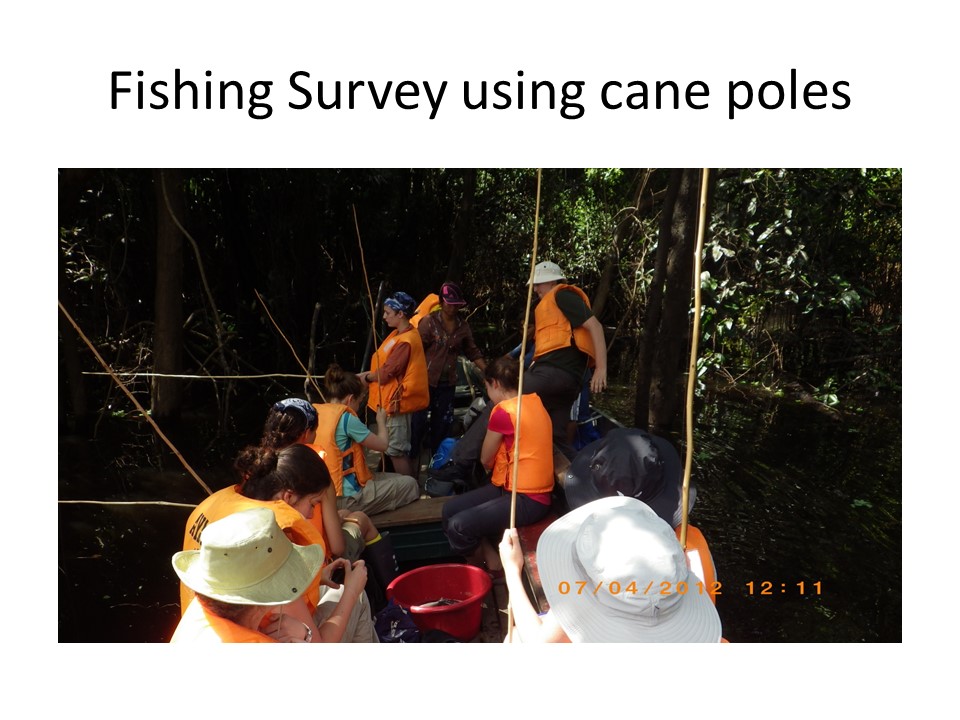

I conducted several types of sampling while on the expedition. I was able to collect fishes and record the natural soundscape during regular day-time fishing surveys conducted

by Operation Wallacea (N = 25 trips, 21 with soundscape recordings), as well as during my free time from the dock at the base station (N = 31, 3 with soundscape recordings).

Recordings conducted at the base station could only be done when the support ship generators were off due to the noise, but even at other times various noises associated with base

activity precluded soundscape recording (plus I had to sleep sometime...)

I also was able to hire a local to let me tag along on his canoe

fishing trips on 4 occasions when the Operation Wallacea survey paused for a couple days between survey legs (high school and college students sign up for a two week leg of the

survey so there is a short pause in the survey while groups are being exchanged). In addition, I participated on 8 daytime dolphin surveys, and 1 night-time caimen survey where I

recorded the ambient soundscape. Recordings from the deck of the Rio Amazonas were conducted on a few occasions.

|

|

|

Base-station sampling

Fish were collected at the base station primarily by dip-net or fishing. When I arrived, I discovered there were no dip nets at the station which was really frustrating because

there were thousands of fish of all kinds all along the vessel, dock and in the shallows along the shore. Many fish stay at the surface because of low oxygen conditions in the

river, so they are easy to see. Fortunately, I had brought along some mesh bags and was able to hire some of the locals to make me three nets in their spare time. I learned a

long time ago to try and anticipate all kinds of needs when sampling in the field, especially in remote locations. So I brought along little things, that did not take up much

room, but could be used (like MacGyver) to make tools. Anyway, the nets were incredibly useful and many of the students enjoyed using them to help catch fish in their off times.

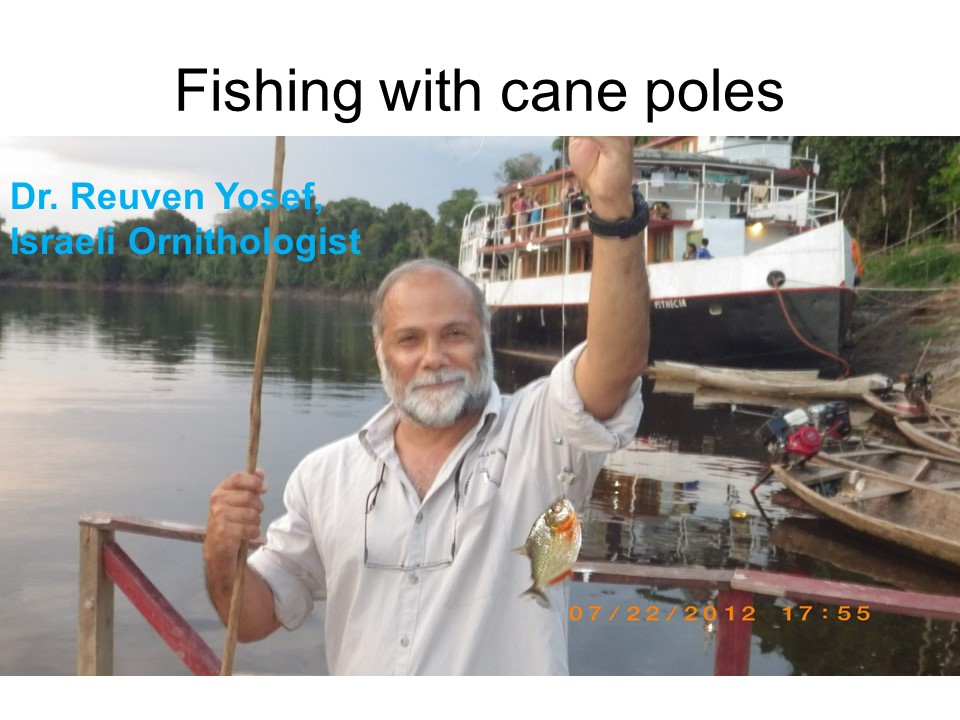

On a number of occasions fish were also captured using the same cane pole method employed by the expedition in their fishing surveys. Basically a reed pole with about 2 m of line

and a single hook, baited with fish or chicken. In the photo above, my friend and colleague on the expedition, Dr. Reuven Yosef catches his first piranha (and if I remember correctly,

his first ever fish). One of my other clever innovations was to construct a minnow trap out of my mosquito hat. It turns out that there were very few mosquitos or biting bugs of any

kind during my stay as I spend almost all my time on the river (in contrast the students going on the various jungle surveys met with plenty of biting insects!). Well the "trap" did

not catch much, but it did catch the only 2 specimens of porthole catfish that I obtained (though many were seen migrating through the area). The dock sampling actually resulted in

the capture of a higher diversity of fishes than observed in the fishing survey which only targeted fish that could be caught by hook-n-line or gill-net.

|

|

|

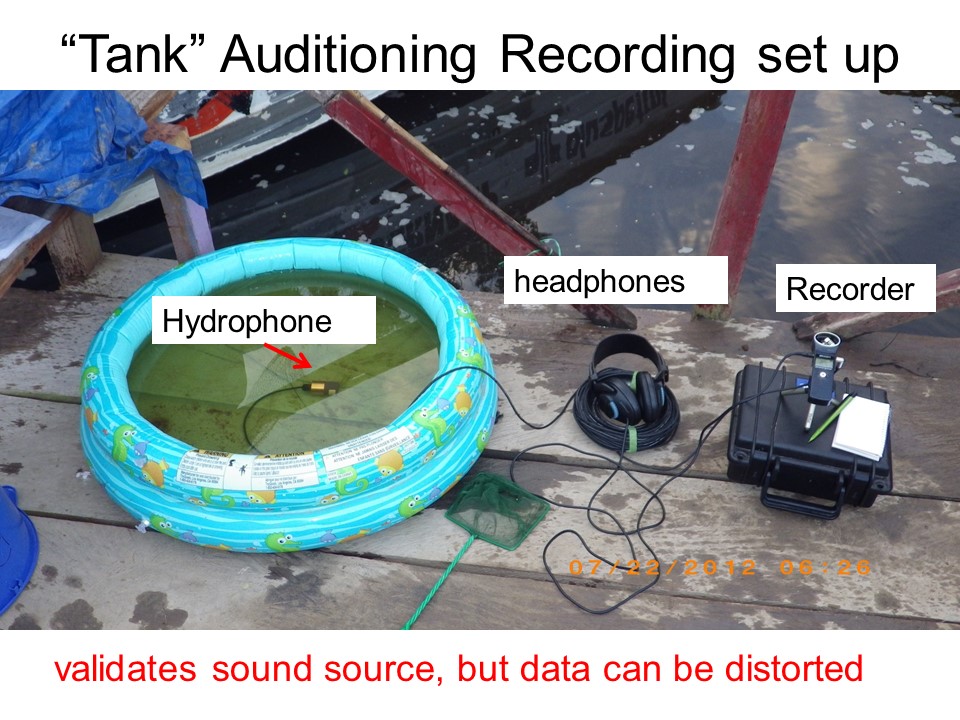

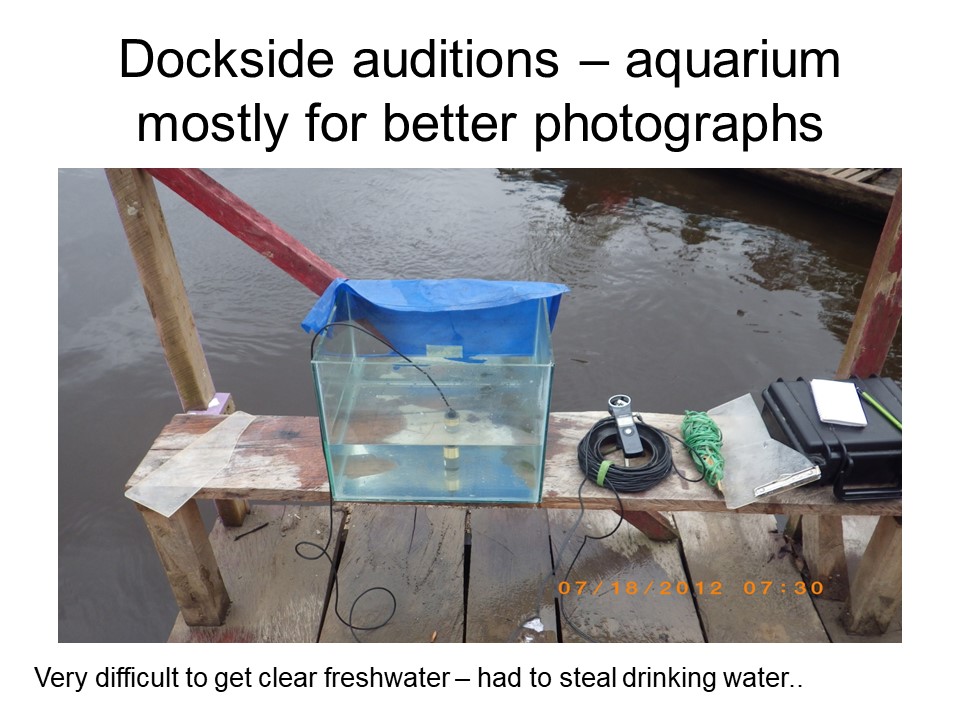

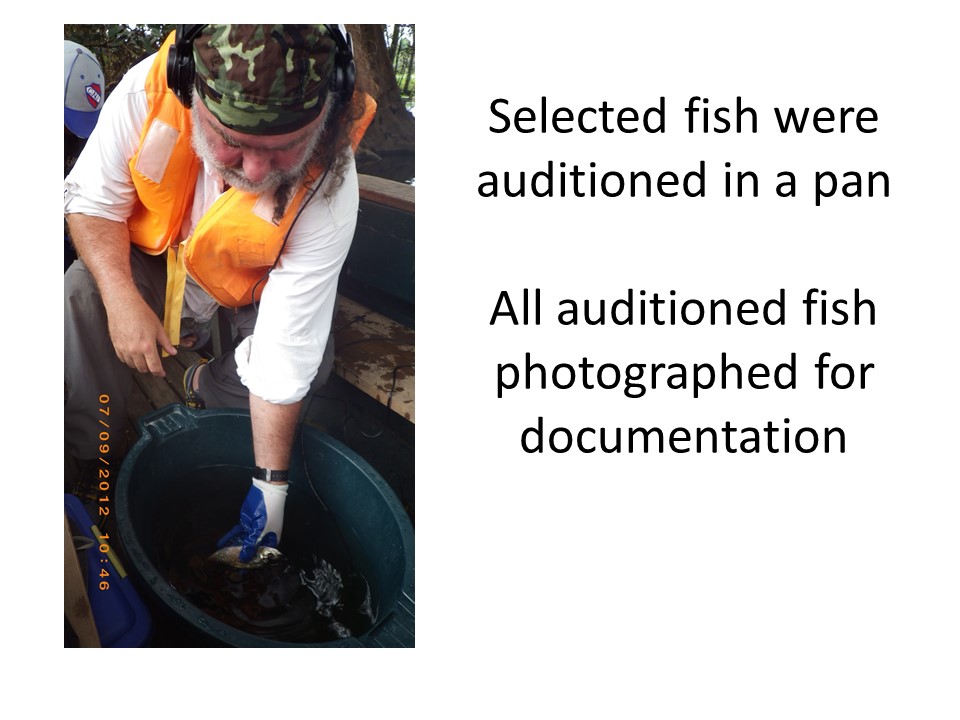

Fish captured during the day or night were held in a small inflatable "kiddy" pool until they could be auditioned (usually between 6 and 8 am, or after 10 pm when the ship's generator were shut down). I'm glad I thought to bring the pool along in my luggage (o.k., os I had four big suitcases...). At other times they would be immediately auditioned after capture. I instructed all the students participating in the survey to put any healthy fish they captured at the base station into the pool so that I could audition them as I had time. Soon, however, the local bird life discovered my little pool and thought it was a nice local restaurant so I had to start covering the pool. Once the locals found out what I was doing they and began to bring me fish to audition, including things I could not get otherwise (like the ripsaw and doncella catfish. They seemed very amused by my efforts and laughed a lot, but were also clearly fascinated. I should say at this time that all our collections were catch-and-release, we were not permitted to remove fish or even fish tissue from the reserve.

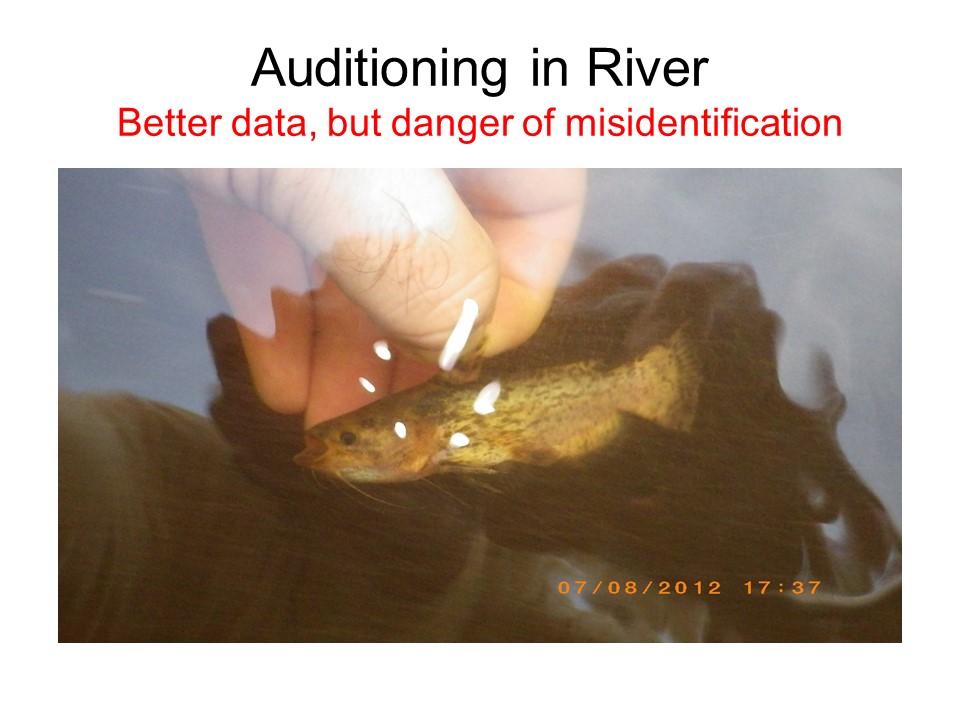

The basic procedure to audition the fish was to first measure and photograph a specimen, then audition it in the pool and/or aquarium by gently holding it underwater near the hydrophone with one hand while taking pictures, recording notes, and operating the recording equipment with the other hand. I would then immediately audition the fish in the same way in the river to get more realistic sounds under natural conditions. Auditioning in the pool or tank, insured that a sound could be accurately attributed to a species and an individual, but resulted in sound distortion due to shallow container effects. In contrast, sound recorded in the river were not distorted, but could be confused with sounds from free-swimming fish. In addition, fish sometimes escaped while being auditioned in the river (ever try to hold an angry piranha underwater with one hand while doing everything else with the other, all while balancing in a small boat filled with high school kids?), so it was important to attempt auditioning in the container first. Species identifications were made in the field or by subsequent examination of photographic materials (thanks to the many scientists who advised me on fish identification from the photos I posted online).

|

|

|

Fishing survey sampling

Fishing surveys were carried out in a small tributary of the Samaria River that drains Huisto Lake (see map above). The expedition conducted two trips per day at randomly selected sites

in the tributary. Fish were collected by fishing with reed poles and with gill nets which were soaked for about 1 hour. Locals were hired by Operation Wallacea to guide the surveys

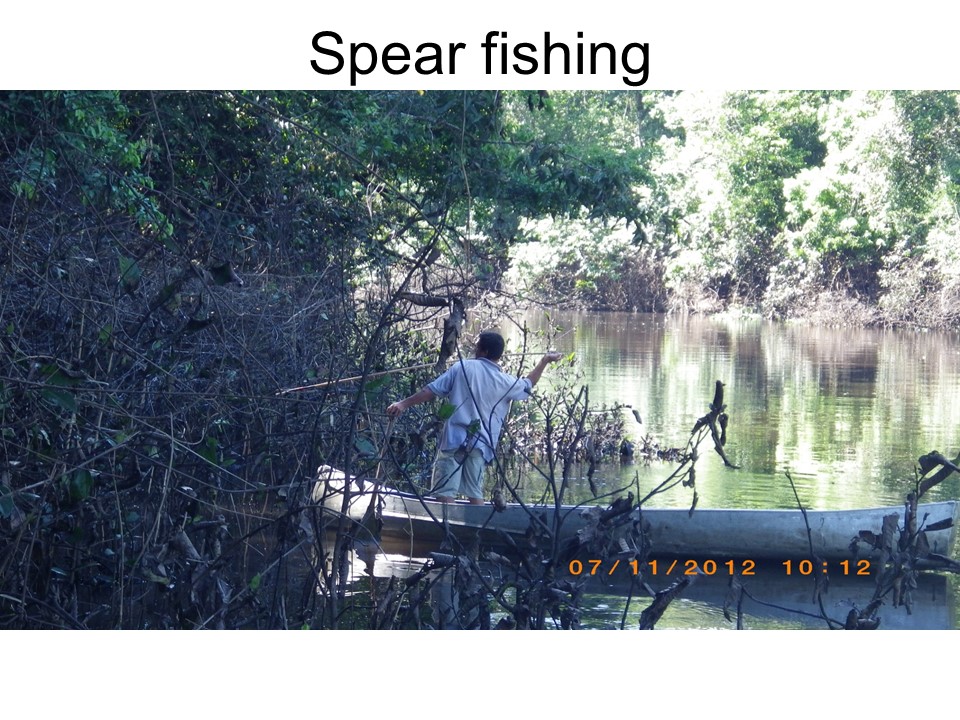

and fish the

gill nets. They also occasionally use traditional spear-fishing methods to capture larger fish (which were usually kept for consumption). As fish were captured by fishing, they held

in a plastic tub until they could be auditioned (almost immediately for hook and line caught fish). Each

auditioned individual was assigned a unique identification number and photographed. GPS position was embedded in each photograph as well as date and time. As in the base sampling

fish were first auditioned in a second plastic tub and then released alive into river.

|

|

|

|

|

Results - Go directly to Amazon fish sounds

|

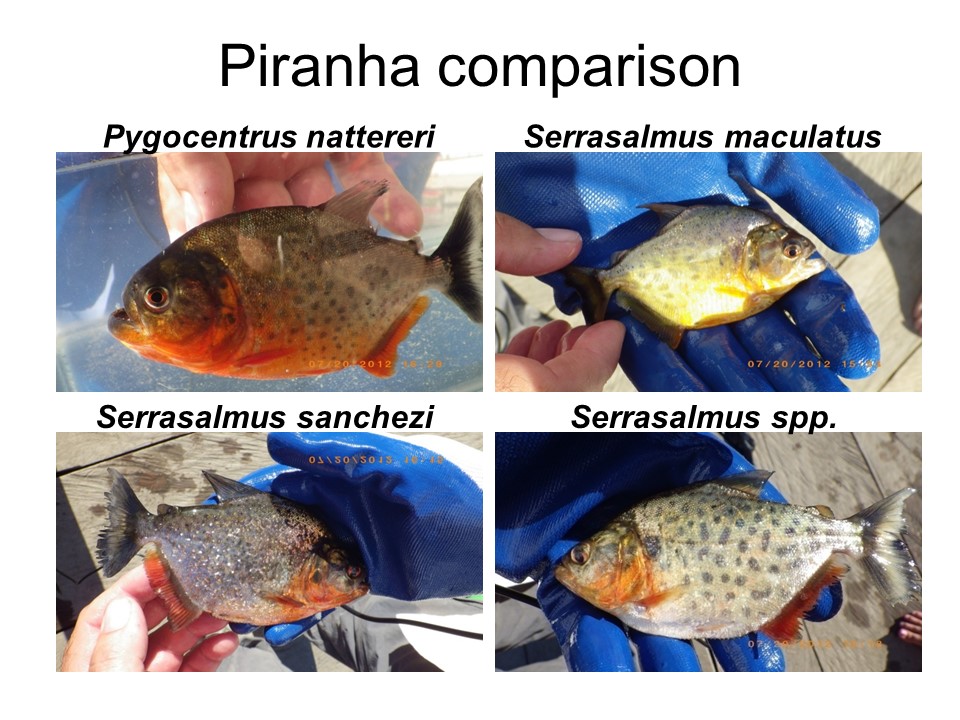

Piranha comparison

Piranha comparison

However, we have completed a comparison of sounds produced by the various species of piranha that we observed. Rountree, Rodney A., and Francis Juanes. 2018. Potential for use of passive acoustic monitoring of piranhas in the Pacaya–Samiria National Reserve in Peru. Freshwater Biology Go to the paper. |

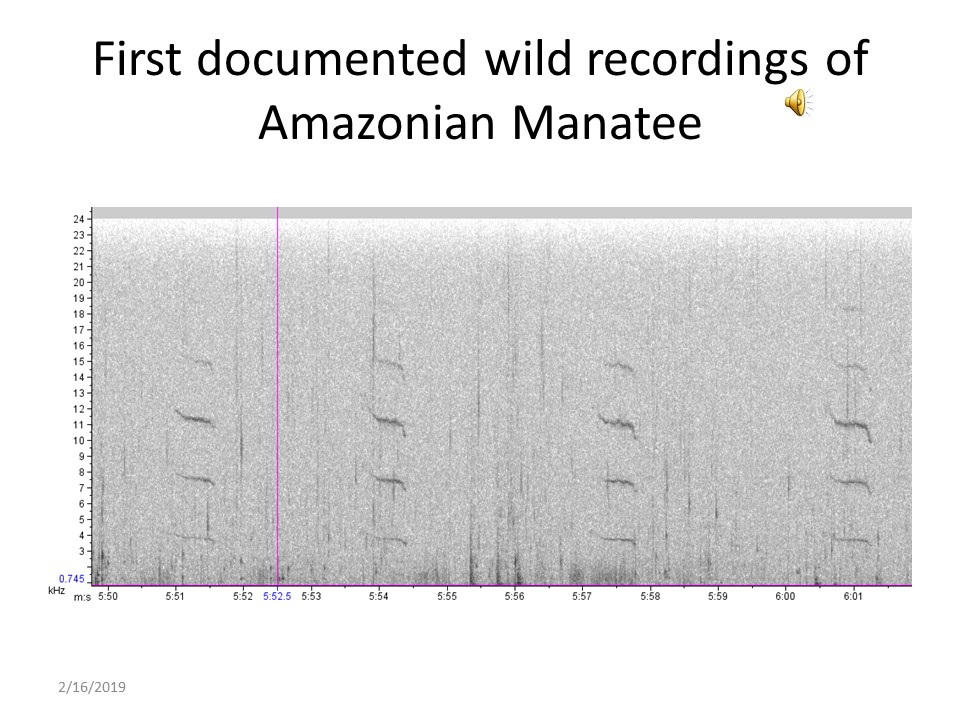

The Amazonian Manatee

When I was planning for the expedition, I had hoped to get recordings of the threatened Amazonian Manatee, Trichechus inunguis. Unfortunately, I never even

saw one during my trip. However, the species behaves very differently from the much larger North American manatees I am familiar with. It is much smaller and

very cryptic, possibly due to centuries of hunting by humans. During the fishing survey on the morning of July 7th, I thought I heard a faint manatee like sound, but

we did not see anything. Later, back at the base station when I was reviewing the day's recordings, I confirmed that I had recorded manatee sounds, so one must

have been very close by. Back in Iquitos at the end of the trip I had the opportunity to attempt to record captive manatees in a rescue center just outside the city, but

they were silent. After returning home, I realized that no one had ever documented sounds of the Amazon Manatee in the wild before. All published recordings were from

captive specimens. So I began contacting colleagues and collaborated with Dr. Sousa-Lima who has been studying Brazilian populations for years. She also

had recordings of manatee in the wild, but none were published. We realized that this was an important contribution and that it was powerful evidence to

suggest that passive acoustic monitoring (PAM) might be a very effective tool in Amazonian Manatee management. We subsequently published a note comparing wild

sounds with captive sounds and suggesting the great potential of PAM for the species.

Sousa-Lima,R.S. R.A. Rountree, M.R.M. Brito, I.M. Carletti, V.M.F. da Silva. 2013. Invisible yet detectable: wild Amazonian Manatees (Trichechus inuquis) can be

monitored by passive acoustics. XI Congresso de Ecologia do Brasil & I Congresso Internacional de Ecologia, Porto Seguro, Brasil; 09/2013

Read the paper

View our poster presentation

Listen the manatee whistles which has been filtered and amplified, but you may want to use headphones.

Download the wav file.

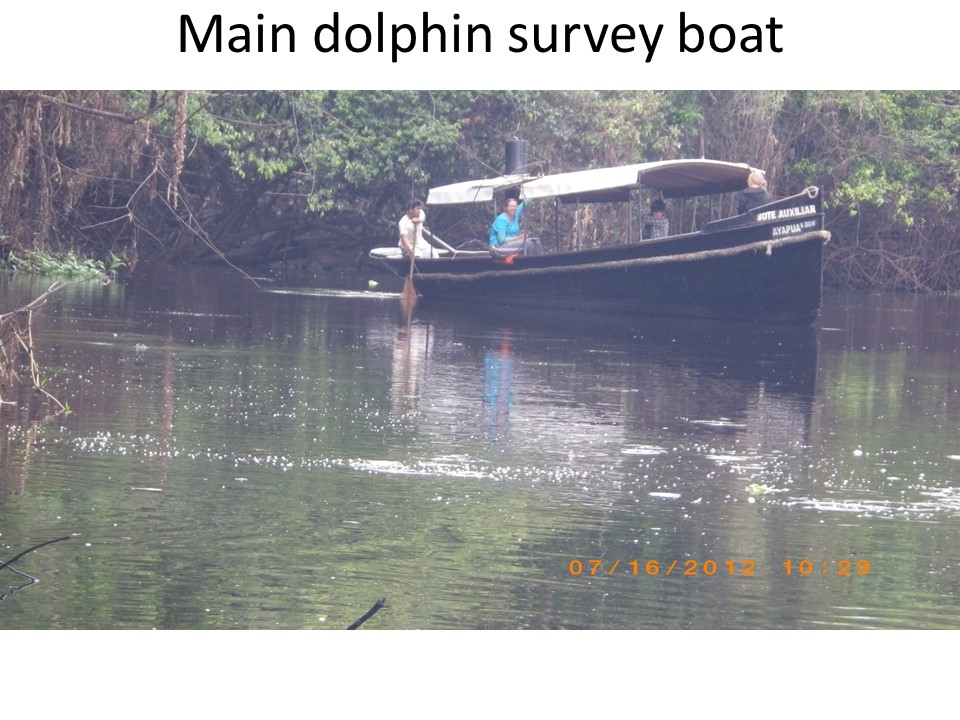

Dolphin Surveys

Dolphin surveys were carried out in a small motorboat that conducted drifting surveys of approximately 2 hours duration. The boat would travel about 5 km up stream of the

base station and then drift downstream, or drift downstream starting at the base station. Both upsteam and downstream surveys were conducted daily. I participated in eight

drifts in which I recorded ambient underwater sounds along the drift. I had hoped to look for possible correlations between dolphin presence and fish sounds. Unfortunately, I

decided to abandon the effort for several reasons: first the movements and activities of students in the boat produced too much noise; second, I was hearing very few fish sounds

in these day-time drifts, and third, I was having so much success with the fishing surveys and dockside sampling that I wanted to focus all my time on them. Despite this, the drifts

were fascinating. Although I have not processed the data, I did get the feeling that the few fish sounds occurred in the vacinity of the dolphins. I also found out it was

virtually impossible to photograph the dolphins as they only very quickly surfaced for air and were gone in a flash. So I started video recording them instead. At the same time

I played the underwater sounds over a loud speaker for the benefit of the students, and so that the sounds could be captured on the video. Watch the attached video to get

an idea of what the drifts were like and what the dolphin sounded like. There were two species of dolphin in the area, most were the pink river dolphin (boto), Inia geoffrensis,

was abundant and could be seen frequently every day. The gray river dolphin (Tucuxi), Sotalia fluviatilis was much less common and I rarely saw one. Although I abandoned

my efforts on the dolphin survey's I do think future studies using similar methods to compare dolphin locations (visually and acoustically) with fish sounds would be very informative.

I recommended that Operation Wallacea consider incorporating passive acoustic monitoring in their dolphin surveys.

Acknowledgements

Rachel Bronstein and Sarah Wylie assisted in the field. We also wish to thank fellow members of the Operation Wallacea Peru

Expedition 2012 and R.E. Bodmer for logistical assistance, including

obtaining all necessary permits within Peru. Operation Wallacea

provided travel funds in support of this project.

A few photos from the expedition

Return to: | TOP |

Copyright © 2019 by Rodney Rountree. All rights reserved

Navigate toolbar: [ Fish Diets | My Photos | Estuarine Research | FADs | Soniferous Fish | My CV | My Youtube | Children's Stories | Fish Facts | My Writings | Home Page ]